Our Stories

Recent Articles

History & Discoveries

A Hallowed Figure in American Art and Culture: the Bald Eagle

The bald eagle is painted, sculpted and carved throughout the Capitol campus. Its white head, wide wingspan and gnarled talons are ubiquitous.

History & Discoveries

Unearthing Capitol Hill's Buried History

Visit Congressional Cemetery and discover the many connections the Architect of the Capitol has to this hallowed ground.

History & Discoveries

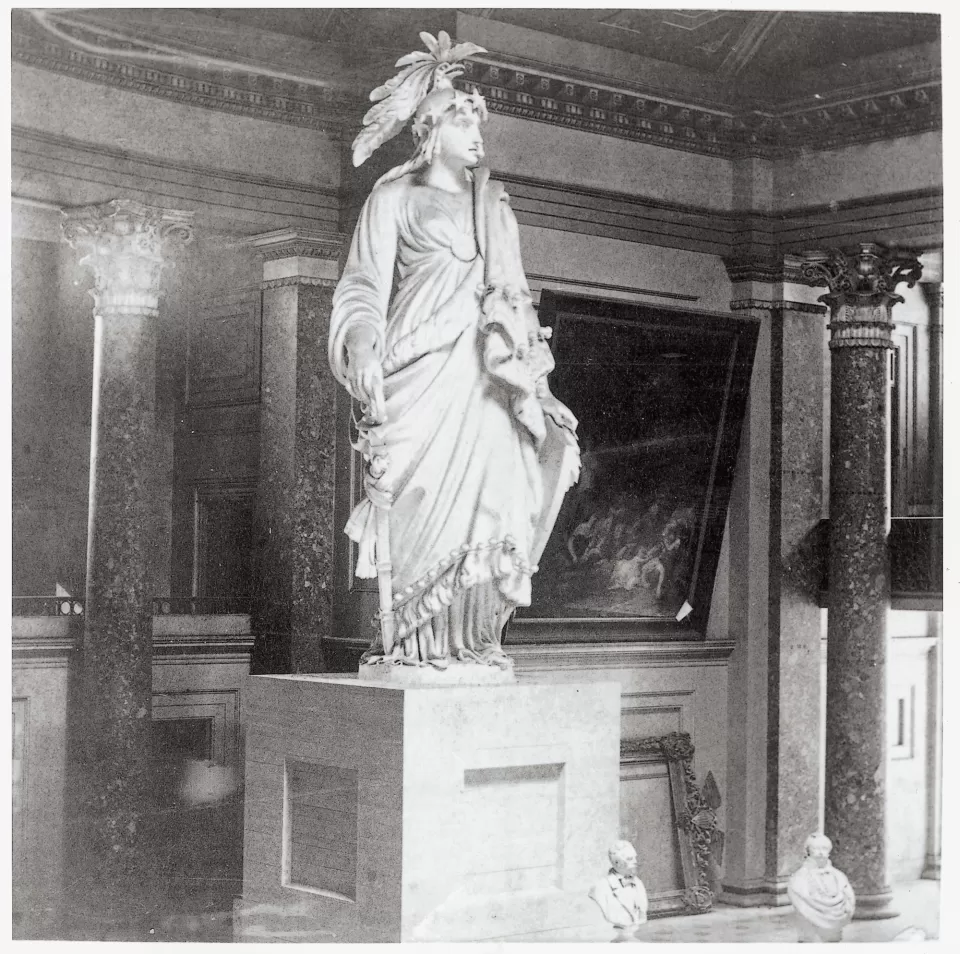

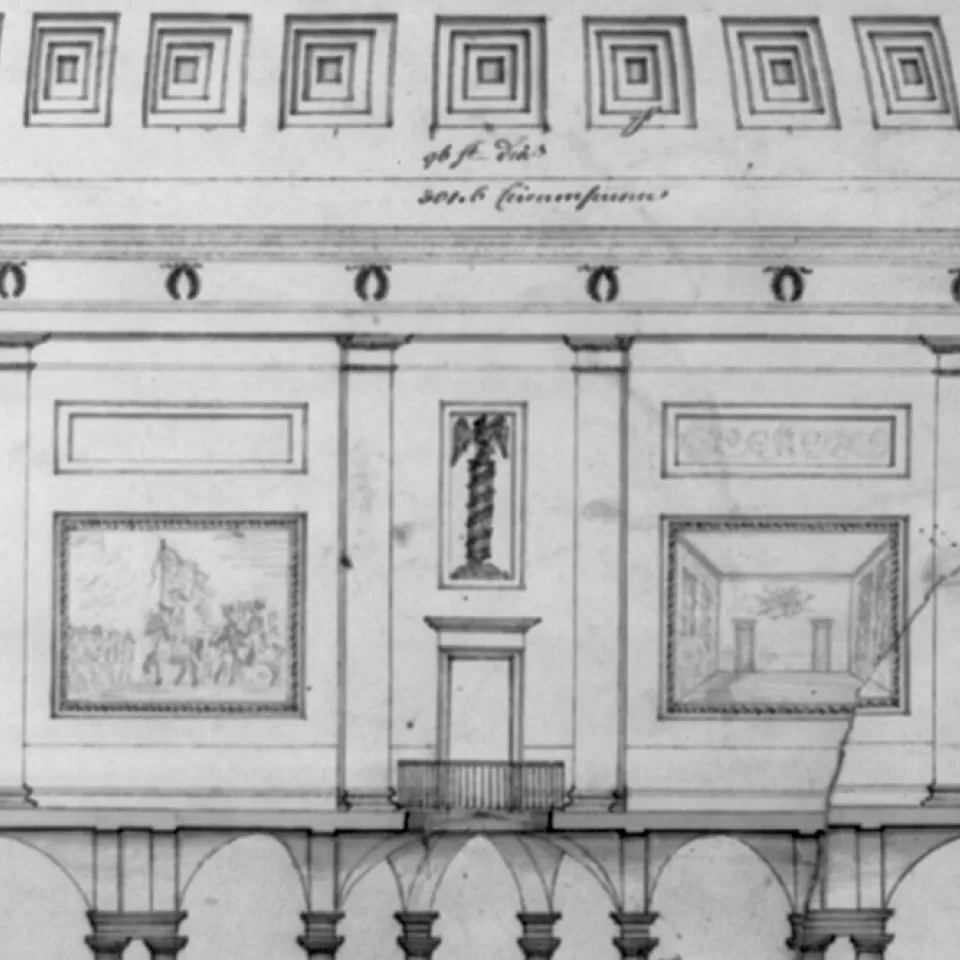

The U.S. Capitol Rotunda: Celebrating 200 Years as the Heart of American Democracy

The Rotunda was completed under the direction of Charles Bulfinch by the time of the visit of the Marquis de Lafayette in October 1824.

History & Discoveries

The Liberty Cap: Symbol of American Freedom

The 2024 Olympic mascot is a conical cap, the Phryge, a French symbol of freedom, but it symbolized freedom in the United States before the French adopted it.

Comments

Nice article! Consider a follow up to this describing and illustrating the Statue's move from Russell to the CVC. I have some pictures I can send you!

Interesting for sure -

The only word I can say is WOW1 what a job great craftsman!

The article serves as a tribute to all who work with their hands.

I have been researching and writing about this Statue of Freedom, also known as Lady Freedom for years and hadn't heard about this slice of her life. Thanks for sharing it.

TJHANK YOU

Add new comment