Our Stories

Recent Articles

History & Discoveries

Capitol Lyrics: "America the Beautiful"

The lyrics of this patriotic song are found easily at the U.S. Capitol.

History & Discoveries

A Hallowed Figure in American Art and Culture: the Bald Eagle

The bald eagle is painted, sculpted and carved throughout the Capitol campus. Its white head, wide wingspan and gnarled talons are ubiquitous.

History & Discoveries

Unearthing Capitol Hill's Buried History

Visit Congressional Cemetery and discover the many connections the Architect of the Capitol has to this hallowed ground.

History & Discoveries

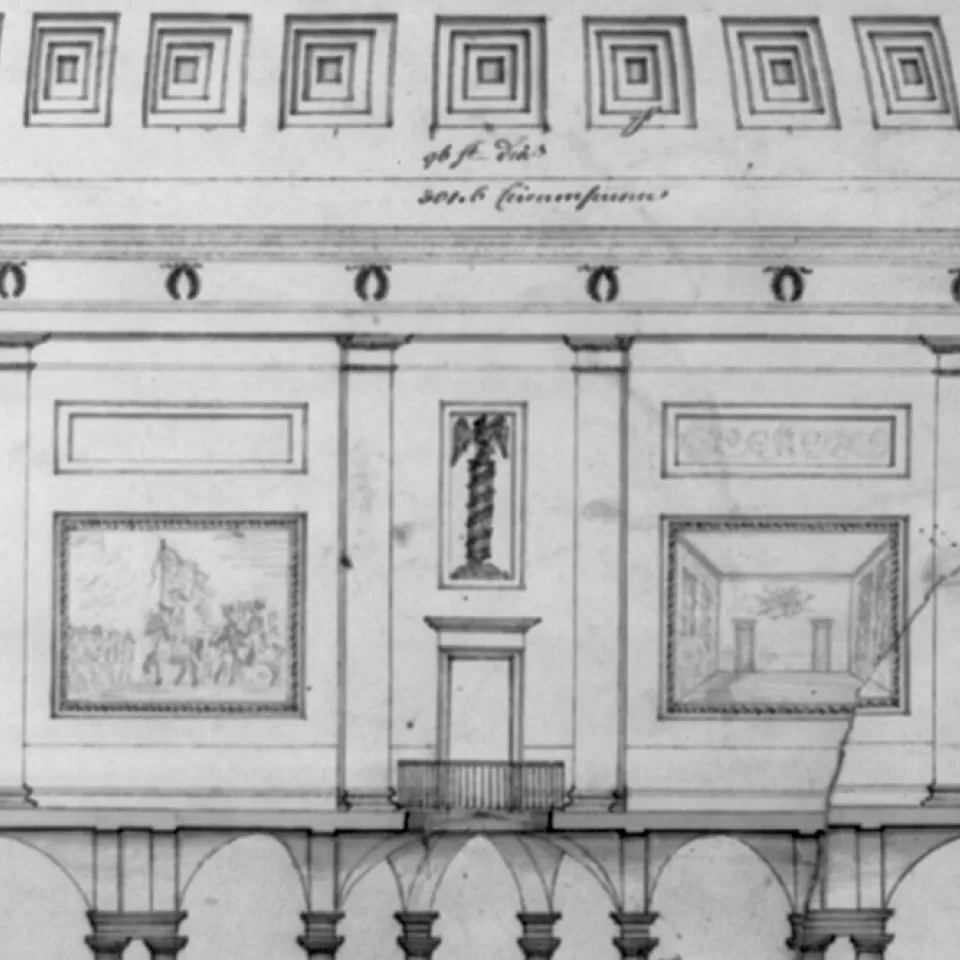

The U.S. Capitol Rotunda: Celebrating 200 Years as the Heart of American Democracy

The Rotunda was completed under the direction of Charles Bulfinch by the time of the visit of the Marquis de Lafayette in October 1824.

Comments

Great article. Learned a lot.

Thank you, Michelle.

Thanks for explaining many terms such as allegories, and the role of woman in Capitol Art. I am writing a book about the Statue of Freedom and will go more into depth with Thomas Crawford and the times when the statue was designed and placed on the Dome. A US Capitol Fellowship allowed for in depth time to research in the Curators office and Library of Congress.

Add new comment