Image Gallery

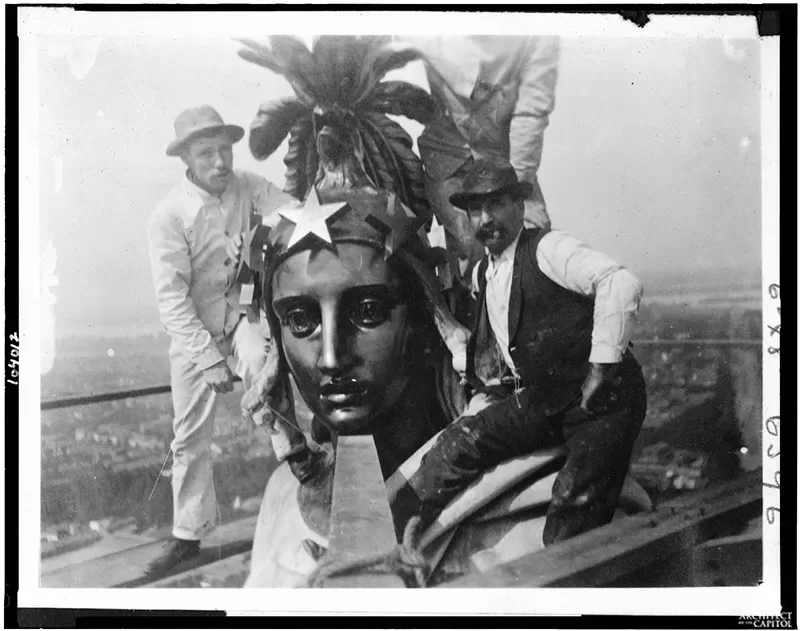

Statue of Freedom is a classical female figure with long, flowing hair wearing a helmet with a crest composed of an eagle's head and feathers. She wears a classical dress secured with a brooch inscribed "U.S." Over it is draped a heavy, flowing, toga-like robe fringed with fur and decorative balls. Her right hand rests upon the hilt of a sheathed sword wrapped in a scarf; in her left hand she holds a laurel wreath of victory and the shield of the United States with 13 stripes.

The helmet is encircled by nine stars. Ten bronze points tipped with platinum are attached to her headdress, shoulders and shield for protection from lightning. She stands on a cast-iron pedestal topped with a globe encircled with the motto E Pluribus Unum (Out of many, one). The lower part of the pedestal is decorated with fasces (symbols of the authority of government) and wreaths. The pedestal is 18-1/2 feet high and almost doubles the total height. The crest of Freedom’s headdress rises 288 feet above the East Front Plaza.

Statue of Freedom does not wear or hold a knitted liberty cap, as would have been expected in nineteenth-century art. The knit cap provided to freed slaves in ancient Rome had been adopted as the symbol of liberty or freedom during the American and French Revolutions and was usually shown as red. The Statue of Freedom's crested helmet and sword, suggesting she is prepared to protect the nation, are more commonly associated with Minerva or Bellona, Roman goddesses of war. The history of the statue's design explains why she wears a helmet rather than a liberty cap. The story of her casting reveals that some of the people who worked to create Freedom were not themselves free.

A monumental statue for the top of the national Capitol was part of Architect Thomas U. Walter's original design for a new cast-iron dome, which was authorized by Congress in 1855. Walter's first drawing showed a 16-foot statue holding a liberty cap on the long rod with which a slave would be symbolically touched during a ceremony bestowing his freedom in ancient Rome.

Construction Superintendent Captain Montgomery Meigs, who was overseeing the artistic decoration of the Capitol extensions, had already engaged American sculptor Thomas Crawford to create other sculptures for the building, including the Senate pediment. He also had Crawford make models for the two bronze doors and for the figures of Justice and History over the Senate door. Born in New York City, Crawford had established a studio in Rome. His portrait statues and groups of classical and historical figures had earned him a reputation as both talented and prolific.

On May 11, 1855, Meigs wrote to the artist at his studio to commission the statue for the dome. Regarding its subject, Meigs wrote, "We have too many Washingtons, we have America in the pediment. Victories and Liberties are rather pagan emblems, but a Liberty I fear is the best we can get."

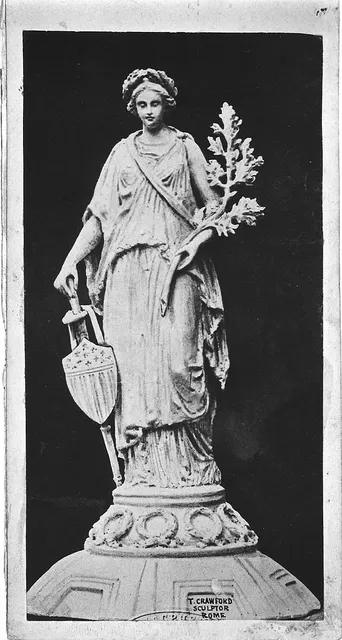

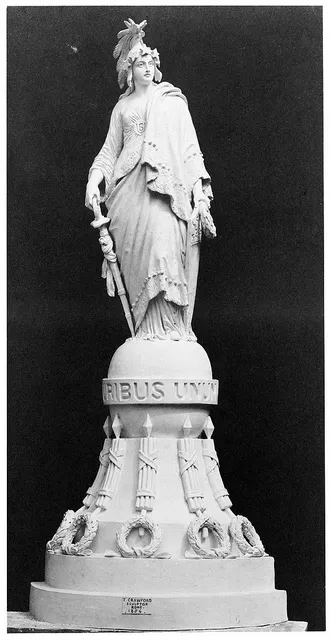

Crawford ended up creating a series of three maquettes (preliminary small models) several feet high and sending photographs of them to Meigs for approval. He described his first design with a female figure wearing a wreath of wheat and laurel as "Freedom triumphant—in Peace and War."

However, when Meigs sent him a copy of the drawing for the dome, Crawford realized that his statue needed to be taller and stand upon a more prominent pedestal. He then sculpted a graceful figure in a classical dress wearing a liberty cap encircled with stars, holding a shield, wreath, and sword, which he said represented Armed Liberty. It was sent to Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, who was in charge of the overall construction at the Capitol. Davis objected to the liberty cap, the symbol of freed slaves, because "its history renders it inappropriate to a people who were born free and should not be enslaved." Davis suggested a helmet with a circle of stars. In response, Crawford designed a crested version of a Roman helmet, "the crest of which is composed of an eagle’s head and a bold arrangement of feathers, suggested by the costume of our Indian tribes." This third design was approved by Jefferson Davis in April 1856.

| Original Design | Second Design | Approved Design |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Crawford executed the full-size clay model in his studio in Rome. It was then cast in plaster in five major sections. He died suddenly in 1857 before the model left his studio, and his widow shipped the model, packed into six crates, in a small sailing vessel in the spring of 1858. During the voyage the ship began to leak and stopped in Gibraltar for repairs. After leaving Gibraltar, the ship began leaking again to the point that it could go no farther than Bermuda, where the crates were left in storage until other transportation could be arranged. Half of the crates arrived in New York in December, but all sections were not in Washington until late March 1859.

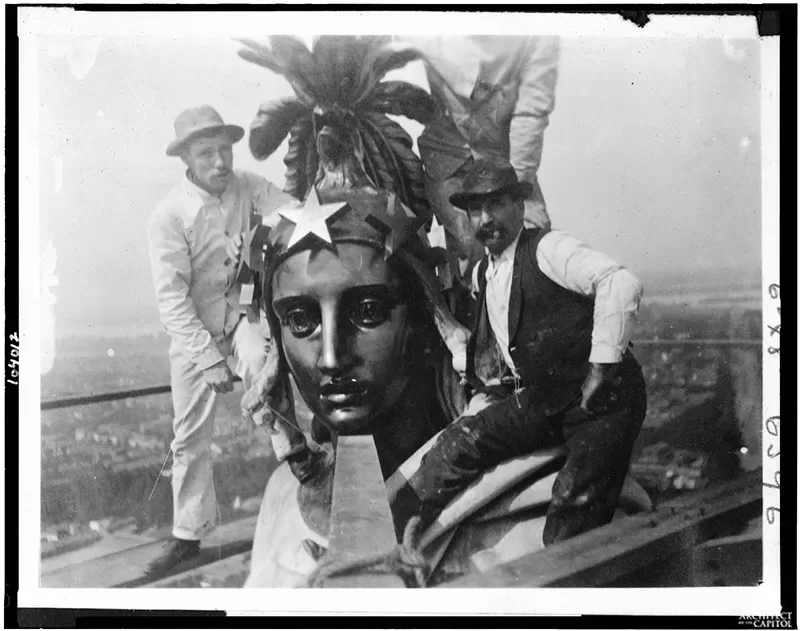

Beginning in 1860, the statue was cast in five main sections by Clark Mills, whose bronze foundry was located on the outskirts of Washington. Work was halted in 1861 because of the Civil War, but by the end of 1862, with the help of the slave Philip Reid, the statue was finished and temporarily displayed on the Capitol Grounds. The cost of the statue, exclusive of installation, was $23,796.82. Late in 1863, construction of the dome was sufficiently advanced for the installation of the statue, which was hoisted in sections and assembled atop the cast-iron pedestal. The final section, the figure's head and shoulders, was raised on December 2, 1863, to a salute of 35 guns answered by the guns of the 12 forts around Washington.

The model of the Statue of Freedom is a piece of history itself. Since its fabrication, the 15,000-pound plaster model has been segmented, moved and stored numerous times. It even left the Capitol in 1890 and was transferred to the Smithsonian where it was displayed in the Arts and Industries Building from 1900 to 1967. Sawn apart and in storage until 1992, the model made a final return to the Capitol that year thanks to funds donated to the U.S. Capitol Preservation Commission.

Architect of the Capitol (AOC) painter General Supervisor Ken Riley was one of the hands-on guys during restoration of the model, which initially took place on the Russell Senate Office Building's loading dock. An AOC Construction Division paint crew exfoliated nearly every square inch of the statue's leaded paint surface. "The biggest challenge was not damaging the brittle — and historic — plaster substrate," says Riley, who spent many hours on the loading dock carefully scraping off the flaking paint.

The paint crew put on a primer undercoat to preserve the original plaster and to provide a barrier coat of protection. Small voids and imperfections were filled with a setting type compound and sanded smooth and level.

Riley also worked on filling and sanding the model’s shield, which he thought looked like it had actually been in a battle. "Because I'd worked on the restoration of the pedestal on top of the Capitol, I'd seen the bronze statue's shield up close with its beautiful concise straight lines. I knew that the plaster model must have at one time looked like that so I ended up spending a lot of time working to correct the alignment of the 13 stripes on the shield."

From the loading dock, the model in two large pieces was crated and transported — with just inches to spare in some of the narrower hallways — to the basement rotunda of the Russell Building.

The Statue of Freedom model remained on view in the Russell basement rotunda until 2008 when the opening of the U.S. Capitol Visitor Center provided a space where visitors could truly appreciate it. It is now the centerpiece of Emancipation Hall, and visitors can see details of the model that would be impossible for them to see from the ground looking up at the bronze statue atop the Capitol.